Does the American welfare system adequately encourage the

poor to achieve self-sufficiency, or is it a “poverty trap” that locks welfare

beneficiaries into a lifetime of dependency? The question has been debated endlessly

with no clear win for either side.

In large part, the dispute turns on a concept known as

the effective marginal tax rate (EMTR) faced by poor and

near-poor households. The EMTR is the percentage of any additional earned

income that a household pays in taxes or loses in government benefits. Critics

argue that high EMTRs leave little incentive to work, and even for those who do

work, they mean that their efforts do little to help them to lift their

disposable incomes above the poverty level. What is the point of getting a job

if taxes and benefit reductions are going to eat up 75 percent or more of your

earnings, even without figuring in expenses like child care, commuting, or work

clothes? Supporters of the existing welfare system argue that punitively high

EMTRs are rare. They emphasize that the current welfare system, despite its

flaws, does raise millions of families out of poverty.

Recent research revives the longstanding debate over EMTRs.

This commentary reviews studies that suggest that despite some changes for the

better, critical segments of the low-income population, especially those with

incomes close to and just above the poverty line, continue to face weak work

incentives. Simply expanding eligibility for existing welfare programs will not

fix the problem. As explained in the conclusion, a more effective approach to

mitigating the poverty trap would be to cash out and consolidate current

welfare programs, replacing them with a combination of universal income

supports, universal child benefits, and wage subsidies for the lowest-paid

workers.

Background: The hypothetical-household approach

One source of past disagreements over poverty and work

incentives has been what we can call a hypothetical-household approach to

calculating effective marginal tax rates. That approach begins by listing

specific benefits that a hypothetical household might receive and taxes that it

might pay as income changes. Suppose, for example, that a certain household

receives food stamps, subject to a benefit-reduction rate of 24 percent;

receives cash benefits, subject to a benefit-reduction rate of 30 percent; and

pays a 7 percent payroll tax. The EMTR for that household would be the sum of

the various marginal rates, in this case, 24+30+7=61 percent. After benefit reductions

and taxes, net income would increase by only $39 for each $100 earned.

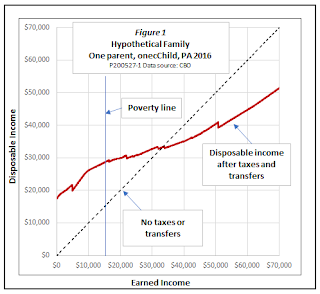

A 2015 study from the Congressional

Budget Office illustrates the hypothetical-household approach. Figure

1, which is based on supplemental data from the CBO study, applies to a

hypothetical family of one parent and one child living in Pennsylvania in 2016.

The household participates in the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), Temporary

Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), SNAP (formerly food stamps), Medicaid,

the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and, as its income rises beyond

the Medicaid level, ACA cost-sharing subsidies for health insurance. The example

also takes payroll and income taxes into account. The figure shows how the

household’s disposable income after taxes and transfers would vary as its

earned income changes.

For this household, the EMTR is lowest in a range from 31 to

54 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). In fact, the rate is actually a

negative 33 percent in that range, meaning that disposable income increases, on

average, by $1.33 for each extra dollar earned. The boost in income is due to

the bonus that the EITC gives to the lowest-paid workers.

The highest EMTRs and the weakest work incentives occur in a

range from 115 to 127 percent of the poverty level. In that range, the

household has reached the phaseout range of the EITC and is also subjected to

substantial benefit reductions for other programs. The EMTR is 80 percent, and

the family gains only 20 cents in disposable income for each dollar

earned.

Defenders of the current welfare system dismiss the

importance of such hypotheticals. For example, Isaac

Shapiro and colleagues from the Center for Budget and Policy

Priorities (CBPP) maintain that extreme EMTRs are worst-case scenarios that

apply to only a small fraction of households who receive an unusual combination

of government benefits. Even then, they apply only in certain narrow income

ranges. By their calculations, fewer than 3 percent of families with incomes

below 150 percent of the poverty line are subject to EMTRs as high as 80

percent.

Who is right here? New research that overcomes the

limitations of the hypothetical-household model provides some answers.

The real-household approach

The new body of research shifts the focus from hypothetical

households receiving an assumed set of programs to real households and the

programs they actually participate in. Studies based on the real-household

approach acknowledge that poor households vary in many ways:

- Characteristics

like the number of children and state of residence that determine the

programs for which they qualify.

- The

degree to which they actually participate in those programs.

- Their

earnings and other factors that determine the benefits they receive from

the programs in which they participate.

The real-household approach both recognizes these variations

and accounts for the number of families that fall into each category.

A series of marginal tax

rate briefs published by the Department of Health and Human Services

in 2019 illustrates the real-household approach. For example, the second brief

in the series focused on 24 million households with children, whose incomes

were less than 200 percent of the poverty line. Among its findings:

- Median

EMTRs increased with income, starting at -22 percent for those with

incomes less than 24 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) and

peaking at 51 percent for those with incomes of 100 to 124 percent of FPL.

- There

was wide variation in the combinations of programs for various households.

For example, the most common combination, SNAP + EITC + Child Tax Credits

(CTC) + Medicaid/CHIP, accounted for just 12.5 percent of poor households

with children.

- Different

combinations of programs produced different median EMTRs. For example, the

most common combination for poor households with children produced a

median EMTR of 42 percent. Adding housing benefits to that combination

raised the EMTR to 63 percent, but that combination applied to only 1.6

percent of such households.

These findings are an improvement over the

hypothetical-household model. They support the contention that we should be

cautious about drawing conclusions from examples based on relatively rare

combinations of program participation. However, they leave a lot unsaid. The

HHS results only whet our appetite for information about the full distribution

of EMTRs above and below the medians, the effects of other benefit and tax

programs not included in the studies, and the variations in EMTRs from state to

state.

Extending the real-household approach

Another study, published even more recently, sheds light on

all these matters. That study comes from David

Altig, Alan Auerbach, Laurence Kotlikoff, Elias Ilin, and Victor Ye. Like

the HHS researchers, Altig et al. follow a real-household approach. They

take into account the observed frequency with which households of various

structures participate in specific welfare programs. However, they go beyond

the HHS studies in three important respects:

- They

consider a larger number of benefit programs and taxes, including premium

subsidies under the ACA, a significant omission from the HHS studies. The

complete list is given in Figure 2.

- They

explore the dispersion of EMTRs within household types as well as their mean

and median values.

- They

calculate both current-year EMTRs, which show how income changes affect

taxes and benefits in a given year, and lifetime EMTRs that reflect how an

increase in current-year income affects net taxes in the future.

The EMTRs are computed using a previously developed model

that the authors call The

Fiscal Analyzer. The analyzer is described as “a life-cycle,

consumption-smoothing tool that incorporates borrowing constraints and all

major federal and state fiscal policies.” The data fed into it come from the

Fed’s 2016 Survey

of Consumer Finances, which includes information on balance sheets, incomes

(including government benefits received), pensions, and demographic

characteristics for a random sample of households.

Altig et al. calculate current-year EMTRs for an assumed

$1,000 addition to current-year income. The current-year EMTR is the change in

net taxes (that is, the change in taxes paid minus the change in benefits

received) in the current year divided by the change in income. The calculation

of lifetime EMTRs is more complex. The first step is to estimate how the extra

$1,000 of current-year income will affect lifetime taxes and resources,

including the effects of saving on future income, wealth, and taxes paid, as

well as the effect those changes in future income and wealth will have on

future benefits received. The second step is to calculate the present values of

those future taxes and resources. Finally, the lifetime EMTR is calculated as

the change in the present value of net taxes — including taxes paid in the

current year — divided by the change in current-year income.

If the household does not consume its entire income each

year, any current-year saving increases future income and wealth, leading to

what the authors call “double taxation.” By that term, they mean that the

household pays taxes on its income in the year it is earned and pays additional

taxes or experiences reduced benefits in future years due to its accumulated

savings. Because of double taxation, lifetime EMTRs are always greater than

current-year EMTRs.

Median EMTRs vary remarkably little across income quintiles

when calculated using this approach. As Figure 3 shows, the distribution of

EMTRs is slightly U-shaped, with lower values for the second, third, and fourth

income quintiles than for the first or fifth. The U-shape is more pronounced for

lifetime than for current-year EMTRs. For both the lifetime and current-year

cases, however, EMTRs are lower for the top 1 percent of all U.S. households

than for the top 5 percent. The bars in both parts of the graph average EMTRs

across all age groups in a given income group.

For present purposes, one of the most striking findings of

the Altig study is the wide dispersion of EMTRs within the lowest 20 percent of

the population. That quintile is critically important for any discussion of

poverty policy. As of 2019, it consisted of households with incomes less than

$26,840, thereby including all officially poor households with four or fewer

members – 91 percent of all poor households. The quintile also includes some

non-poor households with three or fewer members.

Figure 4 divides EMTRs into percentiles within the

lowest-income quintile. It shows that a quarter of these lowest-quintile

households face current-year EMTRs higher than 59 percent. For them, taxes and

benefit reductions wipe out three-fifths or more of any income earned in the

current year.

What is more, any saving by such households is penalized.

Unless the household spends its entire income in the year it is received,

double taxation takes a further bite from lifetime income. The lifetime EMTR is

74 percent for the highest-taxed segment of these households. When double

taxation is considered, at least three-quarters of any extra income

earned by this group in the current year is sooner or later clawed back either

through taxes or benefit reductions.

For the calculation of short-term work incentives, the

current-year EMTR is probably the more important rate. However, when it comes

to the broader concept of a poverty trap, lifetime EMTRs also play a role. A

high lifetime EMTR means that even people who work year after year at low-wage

jobs, and save whatever they can, will find it harder over time to work their

way permanently out of poverty.

Note that for both the current-year and lifetime measures,

the mean EMTR is greater than the median. That reflects the fact that poor

households in the high-EMTR tail of the distribution face “cliff effects,”

meaning that they lose certain benefits all at once when they reach a certain

earnings threshold.

Do EMTRs really matter?

In addition to the controversy over how widespread high

EMTRs are, there is a further controversy over whether high EMTRs really

matter. Altig et al. are careful to avoid that issue. “We seek to understand

Americans’ work disincentives, not the response to those disincentives, a task

we leave for future research,” they write. I agree that labor market behavior

is a complex issue, too much so to treat fully here. At the same time, though,

it is too important to leave without making a few points, which I hope to

follow up on in future commentaries.

Shapiro and his CBPP colleagues take the position that EMTRs

don’t make much difference. Citing a 2011 article by Yonatan

Ben-Shalom, Robert Moffitt, and John Karl Scholz, written for the Oxford

Handbook of the Economics of Poverty, they write that “the behavioral response

[to high EMTRs] is small enough, in aggregate, that it has almost no impact on

the substantial degree to which the safety net lifts people out of poverty.”

Ben-Shalom et al. pose the question in a very specific way,

asking how safety-net programs affect low-income families’ behavior relative to

a counterfactual situation in which such programs do not exist at all. They

carefully review research that bears on this question and find little evidence

that the welfare system in aggregate has major effects on work effort.

However, in a 2016

follow-up, Moffitt adds several important qualifications. He notes that

although work disincentives are relatively small for individual programs, they

can be significant for those who benefit from multiple programs. Although

Moffit doubted that there were enough such families to matter much, the

real-household research reviewed above, not available at the time, suggests

that such cases are far from rare. Secondly, Moffit warns that “work incentives

are more of an issue for families with higher incomes who, when working more,

face both the loss of traditional safety net benefits as well as a phaseout of

[EITC] tax credits.” He concludes that the welfare system as a whole “is doing

very little at the moment to help families help themselves, and this is where

policy could be markedly improved.”

Moffit adds that aggregate behavioral responses to work

disincentives are difficult to detect statistically because other determinants

of whether a low-income family works swamp the effects of EMTRs. I certainly

agree. Improving our knowledge of how EMTRs are distributed across real

households, as recent research has done, is one step toward reducing the

statistical noise. Still, many other factors also cause variations in the

way individuals respond to the incentives and disincentives inherent in welfare

programs.

The availability of jobs, which varies from place to place

and with the state of the business cycle, is obviously one such factor. Also,

as I have emphasized repeatedly in discussions of work

requirements for noncash welfare and guaranteed

jobs proposals, in boom or bust, many of the poor fall into the category of

“hard-to-employ.” These include not only people with little education or job

training, but also those with criminal records, unstable housing, substance

abuse issues, family situations that interfere with regular work schedules,

borderline mental and physical conditions that fall short of actual disability,

and other problems that make it hard to hold a job. Many such people do

repeatedly seek and find work, but their spells of employment are irregular and

often end on a sour note. It is little wonder that small, or even large,

variations in EMTRs have limited effect on their labor-market participation. It

is no surprise that the many hard-to-employ persons in the welfare population

muddle the results of statistical studies.

Statistical results aside, what really bothers me about high

EMTRs is the perverse selectivity with which they reach the highest levels for

the very people who are most likely to respond to labor-market incentives.

Hypothetical- and real-household studies agree that people with incomes from

zero to half of the poverty level – people who work only part-time or only

intermediately, and at low-wage jobs with minimal chance of advancement –

typically face EMTRs that are low or even negative. But if you show enough

stick-to-it-iveness to work full-time at a minimum wage job, or to hold a

steady part-time job at twice the minimum wage, you hit a dead zone. There,

taxes and benefit reductions take the largest possible bite out of anything you

would earn by working extra hours, or seeking a promotion, or making the change

to a different job that might have short-term inconveniences, but would achieve

long-term rewards. To me, piling penalty-rate EMTRs of 60, 70, and even 80

percent on exactly these people – those on the verge of achieving real

self-sufficiency but not quite there yet – is the very essence of the poverty

trap.

It is also worth noting that the relatively low EMTRs that

many households face are due not to good design of existing welfare programs,

but rather, to the failure or inability of many ostensibly eligible families to

enroll in them. That is partly due to the fact that childless households have

limited access to the largest income-support program, the EITC. But eligibility

is not the whole story. It is estimated that

at least 20 percent of families that are eligible for the program do not

actually participate.

Nonparticipation is an even bigger problem for some other

programs. For example, the Urban

Institute found that only a quarter of all families that were eligible

for TANF in 2016 participated – a rate that had fallen by more than 40

percentage points since the program’s first full year of operation in 1997.

Reasons for nonparticipation ranged from difficulty in navigating the welfare

bureaucracy to strict enforcement of work requirements to drug testing. Section

8 housing vouchers are also notoriously hard to get, even for qualifying

families. A guide from the nonprofit journalism group ProPublica details

the difficulties people encounter with waiting lists, documentation, and

finding an apartment once a voucher is in hand.

Advocates for the poor regularly lament these high

nonparticipation rates, and rightly so. If TANF and housing vouchers were

actually accessible to all who met the formal eligibility requirements, and if

EITC were open to childless households, those programs would lift far more

people to a decent standard of living. But ironically, without other reforms,

wider participation in existing welfare programs would significantly increase

the number of households facing punitively high EMTRs. It would reduce measured

poverty, but at the same time, it would make it even harder for low-wage

working families to make those crucial transitions from poverty to permanent

self-sufficiency, and

then on to the middle class.

What should we do?

Can anything be done about the poverty trap? Should we even

try?

Shapiro and the CBPP group do not paint a very optimistic

picture of the potential for change. As they put it,

there are really only two options [for] lowering marginal

tax rates. One is to phase out benefits more slowly as earnings rise; this

reduces marginal tax rates for those currently in the phase-out range.

But it also extends benefits farther up the income scale and increases costs

considerably, a tradeoff that many policymakers may not want to make. The

second option is to shrink (or even eliminate) benefits for people in poverty

so they have less of a benefit to phase out, and thus lose less as benefits are

phased down. This reduces marginal tax rates, but it pushes the poor families

into — or deeper into — poverty and increases hardship, and thus may harm

children in these families. In effect, the second option would “help” the

poor by making them worse off.

In my view, however, there is a third way. Whether or not it

represents a choice that policymakers are ready to make today or tomorrow, it

deserves to be placed on the table as a desirable goal toward which to work.

The third way to fight the poverty trap is neither to

increase nor to reduce benefits within the existing system, but rather, to

defragment that system and then to rebuild it. As Moffit points out, the most

daunting EMTRs are not due to high benefit-reduction rates in any individual

program. Rather, they are attributable to the perverse interactions of

multiple programs, each uncoordinated with the others, giving rise to

overlapping phase-out ranges, and sometimes to abrupt eligibility cliffs.

That being the case, the path to successful reform should

begin by cashing out in-kind programs that cater to specific needs like food,

housing, winter heating, telephone, internet, and the like. Those should then

be consolidated with existing cash assistance programs such as TANF to achieve

what I call a system of Integrated

Cash Assistance (ICA). ICA, together with some separate program to

guarantee universal

affordable access to healthcare, would become the twin pillars of a new,

comprehensive social safety net.

Within the ICA, cash benefits would be subject to a single

income-dependent schedule free of overlapping phaseout zones and cliffs. The

punitively high EMTRs that many poor households face today, especially those at

the critical margin between dependency and self-sufficiency, would be a thing

of the past.

ICA is a concept, not a rigid formula. There would be

considerable room for flexibility in designing the ICA benefit schedule.

Subject to the usual exigencies of negotiation and coalition-building, the

schedule could include:

- An

unconditional minimum benefit regardless of labor-market status.

- Wage

supplements for low-wage workers similar to the phase-in range of the

EITC.

- A

gradual phaseout of benefits beginning at some point beyond the poverty

level, similar to a negative income tax.

- Equal

benefits for people regardless of age, or if preferred, a separate benefit

schedule for children.

Could we afford it? That is the wrong question. ICA has no

inherent price tag. Its cost, like the details of its benefit schedule, would

be subject to political decisions.

As a starting point for discussion, I have described a

baseline ICA that would cost no more than what is now spent on the various

income-support programs it would replace. Such a baseline ICA would provide a

minimum benefit roughly equal to half the FPL – an income level that the Census

Bureau calls “deep poverty” – and would include modest wage subsidies and child

allowances. It would provide stronger work incentives over its entire range

than those faced by low-income households today. Despite its modest minimum

benefit, it would raise a considerably higher fraction of low-income households

out of poverty than does the current welfare system.

When we look at our current welfare system honestly in the

light of the latest research, the picture is not a pretty one, but we should

not give way to despair. There are better alternatives, if we are willing to

work toward them. Even if we cannot get there in a single leap, incremental

changes that are consistent with an overall ICA-like vision can move us in the right

direction.

Reposted from NiskanenCenter.org. Photo courtesy of Pixabay.com.

Will you become our next big winner? Win like, Laptop, Car, Cash, Or more. Enter in our free online sweepstakes, Free online Giveaways and Free Online contests, Don't Miss your Chance. Hurry! Sweepstakes-Online

ReplyDeleteFree online Sweepstakes in US,| Sweepstakes-Online

phoenix summer staycation 2020,| Sweepstakes-Online

Summer 2020 Staycation Sweepstakes,| Sweepstakes-Online

summer staycation ideas, Sweepstakes 2020,| Sweepstakes-Online

sweepstakes websites,| Sweepstakes-Online

Ultimate Summer 2020 Staycation,| Sweepstakes-Online

Ultimate Summer 2020 Staycation Sweepstakes,| Sweepstakes-Online

Ultimate Summer Staycation Sweepstakes| Sweepstakes-Online

I am here to express my profound warm gratitude to the herbal medicine, which I got from Dr. Imoloa. I am now living a healthy life since the past 6 months. I am now a genital herpes virus free after the herbal medication I got from him. You can contact him for your medication Via his email- drimolaherbalmademedicine@gmail.com/ whatsapp +2347081986098/ website www.drimolaherbalmademedicine.wordpress.com

ReplyDeleteI can't still believe i don,t know where to start,my name is Maria Gomez, i'm 36yrs old i was diagnoses of genital herpes diseases,i lost all hope in life but on like any other i still searched for a cure even on the internet and that is where i meet Dr Ogala i could not believe it at first but too my shock after some administration of his herbal drugs i'm so happy to say i'm now cured i need to share this miraculous experience so i say to all other's with genital herpes diseases please for a better life and better environment pls contact Dr ogala via email: ogalasolutiontemple@gmail.com you can also call or WhatsApp +2348052394128.

ReplyDeleteAnd he says he has a cure for HIV after what he did for me i think he can help those with health problems so contact him.

ReplyDelete